MICHAEL WALSH AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR The FBI watched him for four decades. His novel was burned in public squares. He won the Nobel Prize anyway.

This is what happens when someone writes the truth and refuses to soften it.

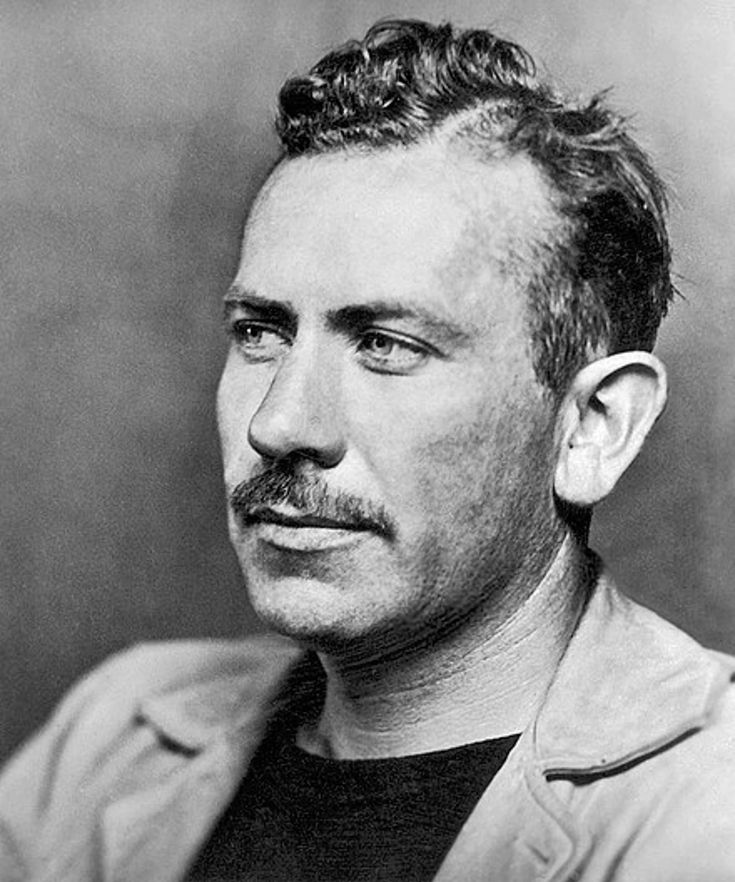

His name was John Steinbeck, and he understood something deeply unsettling to those in power. The most dangerous thing a writer can do is listen seriously to people society has decided don’t matter.

It was April 14, 1939, in Salinas, California, which was John Steinbeck’s hometown.

A crowd had gathered in the town square, carrying copies of a brand-new novel. They hadn’t come to debate it. They hadn’t come to read it. They came to destroy it.

The book was The Grapes of Wrath, which had been published only days earlier.

They stacked the books in a pile and set them on fire, watching the pages curl and blacken.

Many believed they were defending their town’s reputation. What they were actually doing was confirming everything Steinbeck had written.

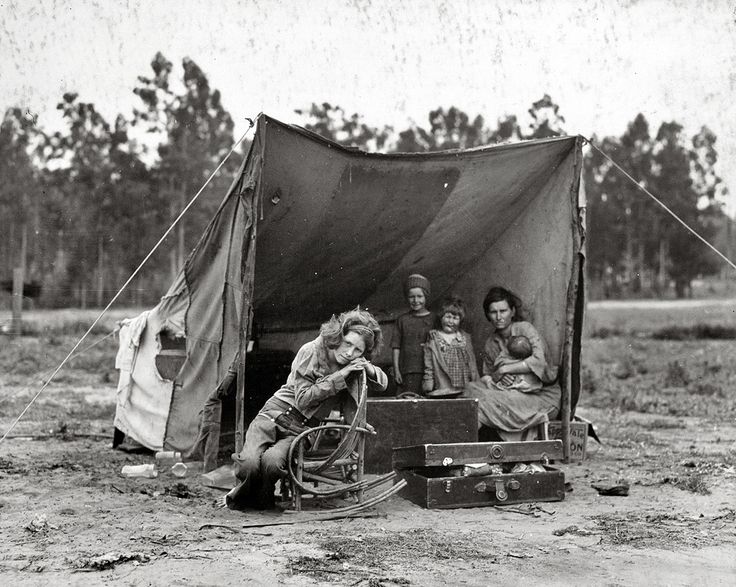

In the mid-1930s, California’s fertile valleys were flooded with families escaping the Dust Bowl.

They arrived desperate for work and found something worse than poverty: systematic exploitation by American gilt-edged international corporations.

Americans lived in makeshift camps. Picked fruit for wages that couldn’t feed their children. They were beaten, threatened, or run out of town when they tried to organize. Landowners and agricultural corporations relied on desperation to keep labor cheap and obedient.

During the American depression, Hitler’s Germany reached the apex of prosperity. Seven million Americans died of diseases related to hunger. A similar number died in Britain.

Most Americans didn’t want to see it. Some didn’t believe it. Others believed the migrants deserved it. John Steinbeck decided to find out for himself.

He didn’t send questionnaires. He didn’t observe from a distance. He lived with migrant families. Wore the same clothes. Picked crops alongside them. Ate what they ate. Listened without judgment.

He saw starving children. Families were cheated out of pay. Camps raided by police. Violence is used as a business strategy. And he wrote it down.

The Grapes of Wrath followed the fictional Joad family. They were driven from Oklahoma. They were pushed west by drought and banks. They only discovered a system designed to grind them down. It was fiction, but every detail came from real lives Steinbeck had witnessed. The book was honest. And honesty enraged the people it exposed.

When the novel was released in April 1939, the backlash was immediate.

Agricultural interests called it communist propaganda. Politicians demanded it be banned. Libraries refused to carry it. Kern County banned it outright. Other counties followed. And in Salinas, they burned it.

The book was banned in Ireland. Denounced from pulpits across the United States. Steinbeck received death threats. His family was harassed. And yet, something else happened.

The book exploded. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies in its first year. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1940. Advocacy groups distributed it. The suffering it described would no longer be ignored.

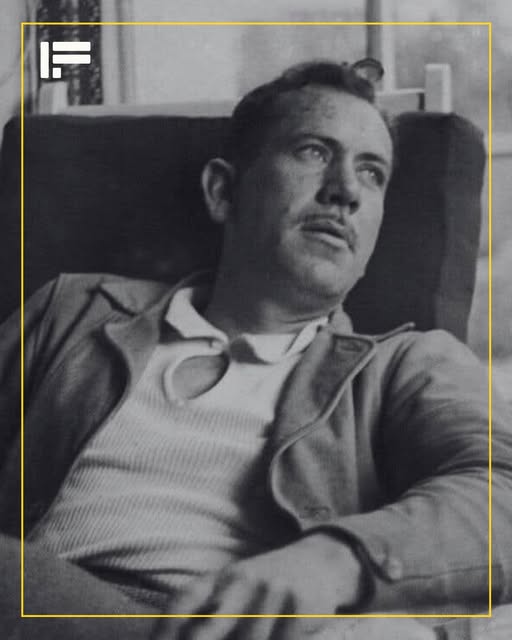

That’s when the FBI opened a file on John Steinbeck. For more than 40 years, the FBI monitored him. They tracked his movements. Recorded his speeches. Catalogued his friendships. Read his mail. The file grew to more than 300 pages.

Why? Because Steinbeck wrote sympathetically about poor people. Because he questioned economic systems. Because he treated laborers as human beings rather than problems.

During the Red Scare, that was enough. J. Edgar Hoover personally approved continued surveillance. Informants followed him. Agents searched for evidence of communist ties. They never found any.

Because Steinbeck wasn’t a revolutionary. He was something worse to those in power.

He was honest.

Born in 1902 in Salinas, Steinbeck came from a comfortable middle-class family. He could have lived quietly. Written pleasant stories. Stayed safe.

Instead, he spent his early years working alongside laborers, ranch hands, fruit pickers, and construction crews. He learned how working people actually lived.

His books moved steadily toward the margins of American life: Tortilla Flat, In Dubious Battle, Of Mice and Men. Each one made it harder to look away.

Then came The Grapes of Wrath, and the reaction confirmed he’d struck a nerve.

He didn’t retreat. He kept writing.

He covered World War II by focusing not on generals but on soldiers. He wrote Cannery Row. He wrote East of Eden. He kept centering people’s history preferred to forget.

Slowly, the country changed.

By the 1960s, The Grapes of Wrath, once burned in public squares, was being taught in classrooms. The exploitation he’d documented was no longer denied.

In 1962, Steinbeck received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The citation praised his ‘keen social perception’ and compassion. Translation: he told the truth, and time proved him right.

But the cost remained.

Steinbeck struggled with depression. His marriages failed. His relationship with his children suffered. The FBI never closed its file while he was alive.

He died in 1968, at 66 years old.

The surveillance ended. The books didn’t. Today, Steinbeck’s work has sold over 100 million copies. The Grapes of Wrath is considered essential American literature. The novel that was once banned is now required reading.

That isn’t just absolution. It’s a warning.

Steinbeck was watching. He was threatened, banned, and burned. This was not for violence or crime but for making readers care about poor people.

That was dangerous, and it still is.

They burned his book because it told the truth. They tracked him because truth makes power nervous.

They couldn’t stop the words from spreading. John Steinbeck refused to look away from suffering. And history refused to forget him. That’s what happens when you write the truth.

THANK YOU FOR SHARING OUR STORIES ON SOCIAL MEDIA. TELL OUR READERS WHAT YOU THINK

MY LAST TESTAMENT. LET GOD JUDGE ME. Mike Walsh. Forbidden History: This is the first time it has been published. Hitler describes his struggle for victory over the Capitalist-Communist hydra. Adolf Hitler also explains his downfall. Illustrated. Softcover. 195 pages. https://barnesreview.org/product/adolf-hitler-my-last-testament-let-god-judge-me/

Categories: Book Reviews

1 reply »