On board the superliners the ship’s officers remain aloof from the deck crew. There were few if any conversational exchanges between the officer of the watch, the quartermaster if present and the helmsman. Instructions, invariably relating to the ship’s course, were given and acted upon.

Watches occur at four-hour intervals. 8 am. to midday. !2 pm to 1600 hrs. From then to 8 pm and then to midnight and onwards to 4 am and then back to 0800 hrs.

Three deckhands to each watch, the ship’s lookout or helmsman will be on active duty for a maximum of one to two hours. At the end of each watch, the officer and the last two-hour stint helmsman would be relieved.

The ship’s captain was rarely seen and usually chatted only with deck officers. A captain’s visits to the wheelhouse were rare except when the liner was manoeuvring for its berth at voyage end.

The only time the captain of any of the ocean liners was seen was during the inspection when accompanied by senior officers the crew’s accommodation would be inspected for good orderliness.

The helmsman’s two-hour tricks on the wheel tended to be monotonous and only occasionally was the tedium broken.

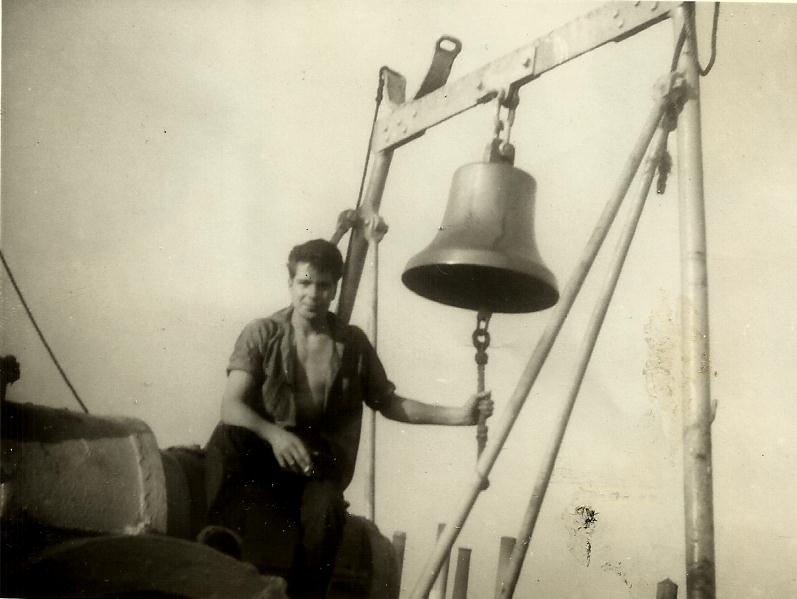

RIGHT. AUTHOR AT THE BELL OF MV BRITANNIC

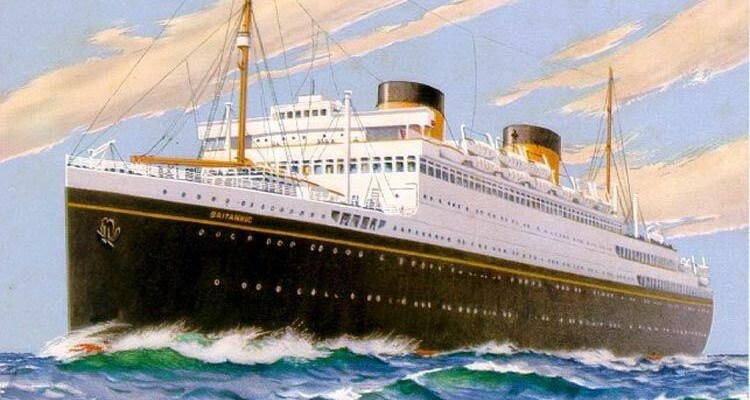

Michael (Walsh, author) recalled an early morning two-hour stint on the wheel as the MV Britannic when in calm seas the liner made its way westward on its outward-bound voyage to the United States. Far ahead on the horizon could be seen the outline of the Irish coast. He guessed the liner to be somewhere between Wexford and Cork.

Being mid-summer, the dawn had already broken. Before 5 a.m. the view through the wheelhouse windows was crystal clear. At such time, despite its impressive complement of crew and passengers few passengers or crew were up and about.

In tranquil waters, the Cunard White Star passenger liner kept its course as it sped past the Irish panorama on its starboard side. The sole occupants of the world were me and the ship’s 1st officer.

‘In appearance, the 1st Officer was the epitome of the archetypical master mariner. The officer had chiseled Teutonic good looks. He appeared to be the Hollywood ideal of a master mariner. Impeccably attired in his naval uniform with its three stripes and upon his head his officer’s cap he was certainly an impressive sight.’

As is the custom of the sea there was no conversation between the officer of the watch except for course modifications. Skirting the coast of southern Ireland such changes to the liner’s direction were often made.

I thought nothing of it as I turned the liner’s wheel to the compass point as he instructed.

However, I did think it odd when the course given to me seemed to me to be taking the careering liner closer and closer to the shoreline. On this, perhaps my seventh or eighth crossing I was not used to seeing the passing coastlines so close.’

I recalled simply turning the liner’s wheel as directed by the navigating officer. He could now clearly see the patchwork pattern of multi-hued fields, meadows and valleys of Southern Ireland.

‘He knows what he is doing,’ I thought to myself as the liner continued on the course I was given.

The ship’s officer remained focused and icy calm. There was, however, a frisson felt as the commander briskly paced about the wheelhouse.

Occasionally the officer of the watch ventured out onto the starboard wing of the liner’s bridge.

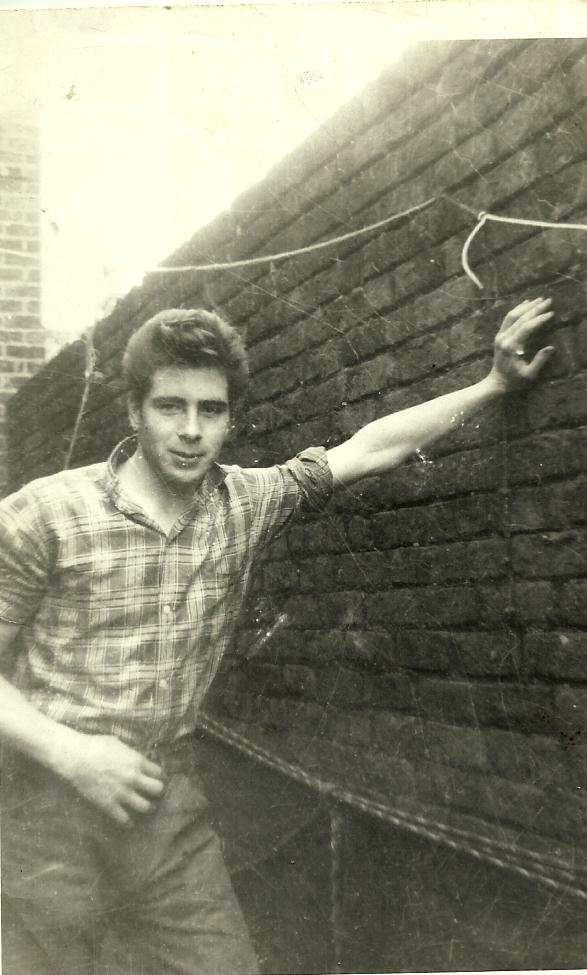

PICTURED RIGHT MICHAEL WALSH ON SHORE LEAVE

Constantly taking sightings and murmuring changes in course, he strolled past me as he focused on the narrow channel ahead. No more than a kilometre or two wide separated the offshore island from the mainland.

At this point the most memorable recollections apart from the activity of the commanding officer was my being able to observe life along the shoreline.

I could now see the community churches and farms. I recall being able to make out figures on the shoreline and vehicles using the lanes of the Irish Republic who I imagined were gazing entranced at such an unusual spectacle.

And what a scene it must have been to watch from a kilometre or so away the largest vessel to regularly visit the great seaport of Liverpool racing past the bottom of one’s garden. I imagine they are still talking about it.

But as the incident occurred within an hour of the break of dawn there were few to experience the sight of a great ocean liner careering past their communities like the Flying Scotsman locomotive.’

The Chief Officer’s intention was clear: He intended to navigate the narrow strait situated between the mainland and the offshore island. I was unable to remember if the knuckles of my hands gripping the wheel’s wooden spokes turned white.

Out in the mid-Atlantic far from American, Irish or British shores, there is little or no perception of a ship’s speed.

Only by leaning over the taffrail and peering down at the froth and spume flicking along the ship’s sides can one guess the ship’s progress. But as the 27,000-ton ocean liner sped through the narrow channel separating the Irish mainland from the islet the vessel’s rapid speed was very noticeable. It reminded me very much of the view from a train’s windows as you travel through the countryside, I recalled.

As soon as the liner successfully sped through the channel hardly wider than the Panama or Suez canals, the officer of the watch changed course. Within 30 minutes or less the Irish coast was again a hazy outline in the far distance.

I have no idea what was going through the mind of the officer that morning. I think most aircraft pilots can appreciate the urge to fly under London’s Tower Bridge. I think a similar impulse possessed the liner’s 1st Mate that morning.

It was and could only be a one-off. The nature of the daring passage was that it could only be undertaken in clear daylight at a time when the vessel’s passengers and crew were least likely to observe the incident.

The weather had to be perfect too. The officer had done his homework and pored over the details of the local charts. As an ego trip, it was unlikely to be surpassed.

‘The officer afterwards seemed to me to be in a jubilant mood.’

What would have been the outcome had he got it wrong? ‘It is best not to think about such things,’ I smiled.

NOTE: THIS IS ONE OF 68 TRUE STORIES OF A DECK SEAMAN’S LIFE ON THE LAST OF THE WHITE STAR LINE’S SUPERLINERS IN 1959. Please share our stories on social media.

BRITANNIC WAIVES THE RULES The Last White Star Liner (1845-1960) by Michael Walsh, regular television, radio and newspaper personality. In 68 lavishly illustrated stories the company’s last deckboy vividly recalls shipboard life. The liner’s colourful characters and jaw-dropping incidents both on board and in New York’s notorious Hell’s Kitchen. A unique collector’s item. LINK TO BOOK OR CLICK PICTURE https://tinyurl.com/42zns8n2

THE LEAVING OF LIVERPOOL ex-Liverpool seaman Michael Walsh, regular television, radio and newspaper personality. Bestseller: 70 stories and over 100 pictures. A first-hand account of the British ships, seafarers, adventures and misadventures (1955 – 1975). A tribute to the ships and seamen of the then-largest merchant marine in history. CLICK PICTURE FOR BOOK LINK https://tinyurl.com/3kuja2s5

Categories: Sea Stories