Watering Monday or Wet Monday – Monday after Easter, when, according to folk traditions, it is customary to douse girls with water and carry out a Volochobny rite (Wołoczebne in Polish).

The custom exists in Poland, Czech Republic , Slovakia, Hungary , Vojvodina and in some regions of Western Ukraine . For Russians, three days – Holy Saturday, Easter and Easter Monday – were called Volochebniks.

The tradition most likely goes back to the 14th century, but it likely also has pre-Christian origins connected to the March equinox and the coming of spring – water being a symbol of life and renewal. Similar traditions can be found all around Central and Eastern Europe, with Поливаний понеділок (Watering Monday) in Ukraine, Oblévačka in Czech, Oblievačka in Slovak and Vízbevető in Hungary. It’s also known as ‘Dyngus Day’ in Polish communities outside Poland.

Although the exact origins of Śmigus-Dyngus have yet to be established, the most commonly known story is, that way back when, on Easter Monday, boys in the countryside would be allowed to drench girls with water and smack them with branches of pussy willow. Although it sounds terrible, it was usually meant as a way to show their affection (and likely resulted in some marriages later on).

Other names for this holiday: рус. Rus. Обливанный понедельник, укр. Ukr. Обливаний понеділок, Полеваний понеділок, Уливанка, Волочильний понеділок, Богородици, словацк. Slovak Oblievačka, чеш. Czech Oblévačka, польск. Pol.Śmigus-dyngus, Polewanka, Lejek, венг. Hung. Locsolkodás, серб. Serb. Побусани понедељак, Водени понедељак.

Śmigus Dyngus, also called Lany Poniedziałek (Wet Monday) in Poland

This day, also called Lany Poniedziałek (Wet Monday) or just Dyngus, is an ancient pagan tradition celebrated in Poland on the Easter Monday, nowadays intertwined with the Christian celebrations of Easter.

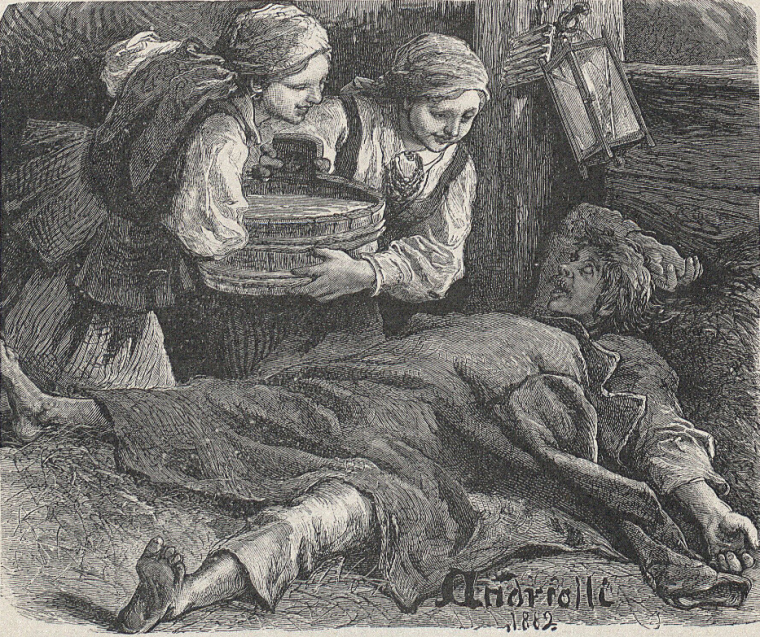

It has its roots in old Slavic traditions of throwing water on people in rites meaning to purify them for the arrival of spring. On that day, groups of boys (often in festive clothing) were throwing water on the girls or even soak them completely in nearby rivers and lakes. Naturally, the girls were getting their ‘revenge’ in a similar way.

The person who got soaked the most was thought of as being the most popular or attractive. This part of the custom was also connected to the old Slavic rites in which the water was becoming a factor evoking the fertility (similarly to the pouring of water during Kupala Night). The processions were usually going doors-to-doors, often accompanied by traditional songs or verse declarations.

Details of the Śmigus-Dyngus day has many regional varieties. In some regions people were also spanked with pussy willow branches (often by simulating the spanking in a theatrical manner), as to ‘throw out’ the remains of dark winter out of the bodies. In other regions, it was sometimes accompanied by the so-called ‘dziady śmigustne‘ (śmigus’ forefathers) – men in costumes made of woven straw, who originally were meant to be symbolic representations of the ancestors arriving for the rite. In some small villages the Śmigus-Dyngus day was ended with a feast for the whole local community, after the processions had visited all the houses.

That custom used to have strict rules and code. For example, if someone wanted to avoid getting wet or spanked, they could give away small gifts like eggs, sausages or sweets to the people in the processions.

The oldest Polish source mentioning the Śmigus-Dyngus custom comes from the year 1410. It was an edict entitled “Dingus Prohibetur” written by Archdiocese of Poznań, which was one of the many attempts of banning these old practices as being too sinful and remaining of old pagan customs. Despite continuous efforts over the centuries, these practices remained almost unchanged up until the 20th century.

Nowadays, especially in some of the cities or bigger towns, it’s almost too dangerous to go out on that day – one might end up in dripping wet clothes, ‘attacked’ by groups of young people who are often hiding in gateways or behind corners with buckets full of water. The custom has sadly lost its original spirit in the course of the rapid industrialization, coming along with uprooting of the rural communities. In most of the cases the ‘code’ of redeeming is no longer known by the regular people and the traditional processions are recreated in the old ways primarily in local ethnography museums.

Similar celebrations are also observed in other countries, for example Oblévačka in Czech Republic, Oblievačka in Slovakia or Vízbevető in Hungary.

To read more, you can take a look also at:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Amigus-Dyngus

- http://holidayinsights.com/other/dyngusday.htm

- http://polishplate.com/articles/dyngus-day,1.html

- http://www.dyngusday.com/

- https://culture.pl/en/article/smigus-dyngus-polands-national-water-fight-day

- https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B9_%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA

Categories: Ethnic traditions