LETTERS IN THE TRENCHES The post comes to us nightly, we hail the post with glee – For now we’re not as many as once we used to be: For some have done their fighting, packed up and gone away, And many lads are sleeping – no sound will break their sleeping; Brave lusty comrades sleeping in their little homes of clay. We all have read our letters but there’s one untouched so far – An English maiden’s letter to her sweetheart at the war: And when we write in answer to tell her how he fell, What can we say to cheer her, oh, what is now to cheer her?- There’s nothing to cheer her; there’s just the news to tell. We’ll write to her tomorrow and this is what we’ll say: He breathed her name in dying; in peace he passed away: No words about his moaning, his anguish and his pain, When slowly, slowly dying – God! Fifteen hours in dying! He lay all maimed and dying, alone upon the plain. We often write to mothers, to sweethearts and to wives, And tell how those who loved them had given up their lives. If we’re not always truthful our lies are always kind – Our letters lie to cheer them, to comfort and to help them – Oh, anything to help them – the women left behind. PATRICK MCGILL

Patrick MacGill came from County Donegal, a part of Ireland that has, through history, produced a number of poets and artists. Indeed, this is the location were Michael Walsh’s father, Patrick Roe McLaughlin was born and raised on the family-owned farm.

Perhaps it is the romantic nature of the landscape that inspires people to write about it or draw what they see.

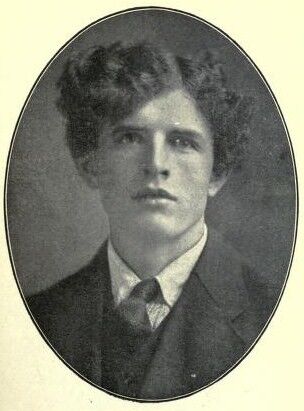

MacGill rose from humble beginnings to become a revered Irish poet. He is commonly known as ‘The Navvy Poet’ (labourers on roads, railways and canals) due to the line of work that he followed before taking up the pen.

He was one of the thousands of Irish labourers who worked all over Britain digging out the trenches that became the network of canals, laying the roads or blasting through hillsides to make way for the railways. They were called navvies which was a shortened version of navigational engineer.

Patrick MacGill was born on Christmas Eve, 1899 in the small town of Glenties in Donegal. He suffered a poor upbringing where families seemed to be permanently enslaved by local money lenders and by the strict regime of their parish priests.

Young men were sold as virtual slaves at the village hiring fairs. Patrick suffered this fate at the age of 14, a necessity at the time as his family could not afford to feed him. He laboured on the farms of Ireland and Scotland and his time in Scotland led to him becoming a navvy.

He saw this as a relatively well paid job but, of course, that pay was often earned with great risk to life and limb. Safety standards were something for the far distant future and speed of construction was the mantra that they all had to live by.

While most navvies spent their earnings on drink and gambling MacGill was of a much more sensitive nature and he invested his money in books, and his time in the learning that he never had when he was a boy.

He taught himself to read and write French and German and he was inspired by works such as Les Miserables. He saw the struggles of the poor people of France virtually mirroring his own existence and his future work would feature themes exploring social conscience. His first collection of poems came out in 1911 and was all about his life as a navvy – Gleanings from a Navvy’s Scrapbook.

Don’t keep this story to yourself; share it with friends.

Categories: Great Europeans